What is Jewish Dance?

For readers interested in the development of folk dance and, to a lesser extent, modern dance in Israel, Seeing Israeli and Jewish Dance, edited by Judith Brin Ingber, a dance scholar who has written widely on Israeli dance, is a valuable resource. The 19 chapters, many reprinted from earlier publications, are generally written at a high scholarly level. Nine of them discuss Israel and its Yemenite, Kurdish, and Ethiopian communities. One piece, by Ingber herself, contrasts Nazi and Zionist views of the Jewish body. Two chapters deal with American Jewish choreographers, one with a major Jewish choreographer for the Russian ballet, and another with a veteran Polish Jewish dancer living in America. There is even a chapter describing Jewish dancing masters in Renaissance Italy.

All this diversity may be too much for a single volume, even a copious large-format one such as this. In America, largely post-Holocaust Jewish choreographers, who were not usually involved in Jewish community dance practices, nevertheless created performance pieces representing crucial events or values connected with Jews. In contrast, the Zionist national enterprise felt a need to invent dances and dance practices that would not just represent but mobilize the Jewish people. In recent times, different Jewish ethnic communities had entirely different motivations for dance and usually shared little or nothing with one another.

An editor addressing such a broad topic must apply a clear analytic framework, balancing a focus on communities exhibiting "Jewish" dance practices against attention to individual attempts to represent those practices using the universal language of artistic stage choreography. Ingber does not show enough awareness of the fundamentally different motivations and antecedents of these differing types of dance. Instead, her discussion of "Jewish dance" begins with the Bible and seeks to find in it values that all Jewish communities preserved. In fact, while dance was a significant element in ancient Hebrew culture and merits prominent mention in any historical treatment of Jewish dance, this knowledge needs to be heavily supplemented by an ethnographic appreciation of how Jewish communities related to this past, if at all, and to one another.

Ingber shows no interest in recent attempts to define the cultures of Jewish communities. Therefore, she has no reasoned way to discuss the question of which modern Jewish communities were socially and demographically able to create dance forms significantly different from those of the dominant Gentile culture. In a short section on "gesture" and in her interviews, especially one with Yiddish dance star Felix Fibich, she correctly notes that some Jewish dance gestures originate in Torah study practices and prayers. But she fails to place gestural practices within the context of living Jewish languages, a question close to the core of the Jewish choreographic issue. It is not Ingber but Giora Manor, in a reprinted essay of 25 years ago, who observed, "[T]he similarity between Yemenite and Hasidic dance that [A.Z. Idelson, a Jewish musicological pioneer] found astonishing lies in the use of improvised hand movements and in the ecstatic but at the same time introverted dance. . . ."

Ingber has more interest in and familiarity with stage dance than with dance ethnography. Seven chapters are devoted to or narrated by choreographers, but there are only three on dance ethnography: Shalom Staub's classic study of Yemenite dance in a 1970s rural Israeli community, Ayalah Goren's well-balanced study of Kurdish dance in Israel, and Jill Gellerman's analysis of Lubavitcher girls dancing in New York. Yet Goren's work makes no mention of the dancing of the majority Muslim Kurds of Iraq, Iran, or Turkey, although Kurdish dancing in Turkey, at least, is quite accessible. While scholars working in Israel may not have access to relevant material from neighboring countries, it is parochial for a U.S.-published book not to mention the largely shared dance culture of Muslims, Jews, and Christians in Kurdistan. In Yemen, the differences between Jews and Arabs, which can be significant, are mainly related to the hand gestures in solo and "couple" dancing by Jewish men.

There are several fine articles about major Jewish choreographers, such as Janice Ross's piece on Leonid Jacobson and Nina S. Spiegel's piece on Yardena Cohen. The interviews with Sarah Levi Tanai and Felix Fibich capture these figures' verve and creativity. Yehuda Hyman's short piece "Three Hasidic Dances: a Personal Journey" explains how an American-born son of Holocaust survivors integrated Hasidic dance into his own choreographies. But the long chapter "The Roots of Israeli Folk Dance," based largely on interviews with choreographers, is hagiography. In introducing her interviews, Ingber says, "It is a unique aspect of Judaism that we can remember and glorify our prophets and teachers." She calls them "modern-day tzaddikim." But if we Jews revere early Zionist choreographers as prophets or saints (tzaddikim), there is not much room for critical review.

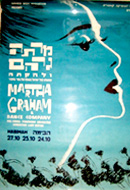

Moreover, major Jewish choreographers from Russia and Eastern Europe get short shrift. The brilliant Russian Jewish choreographer Benjamin Zemach, brother of the founder of Habimah, the national theater of Israel, and an associate of Martha Graham, is mentioned only twice. The Polish-born Nathan Vizonsky, the most prominent Yiddish choreographer in America, is passed over in total silence. The extraordinary Baruch Agadati from Russian Bessarabia, the first artistic dancer in Palestine and Israel's first filmmaker, is mentioned several times; but there is no chapter on his artistic career. What Zemach, Vizonsky, and Agadati had in common was their grounding in the dance practices of East European Jews and their internationally recognized artistic success. Their omission from a book purporting to present "Jewish dance," especially stage dance, cannot be justified.

The articles on Leonid Jacobson and Yardena Cohen present the struggle of two talented Jewish dancers to express their own culture in the face of opposition from an ideologically driven political establishment—in Jacobson's case Soviet censorship, in Cohen's case disapproval by European Zionism. Their ultimate success reflects both their tenacity and shifts in the cultural and political winds. The lives of Felix Fibich and Judith Berg also show extraordinary struggles against censorship and even physical danger, overcome through a combination of talent, strategic skill, and sheer luck.

Symptomatic of Ingber's failure to develop a definition and identification of Jewish dance practices is the fact that she offers no coherent treatment of the Ashkenazim, 90 percent of the Jewish people before the Holocaust and 80 percent of Jews even today. It is traditional Ashkenazic dance, not only "Hasidic" dance, that preserved and developed Jewish gesture as a fundamental expressive element. Ingber fails to present Lee Ellen Friedland's seminal "Tantsn iz Leben: Dancing in Eastern European Jewish Culture,"¹ which remains the best introduction to the subject. In her "Addendum" to Elke Kaschl's article "Beyond Israel to New York," Ingber correctly lists the major dance teachers and dancing sites for Yiddish and Ashkenazic secular dance. But she gives a garbled description of the major East European Jewish dances; her glossary omits almost all Ashkenazic dances, including the freylekhs, the sher (the subject of excellent work by Hankus Netsky), and the bulgar, one of the dominant dances among American Ashkenazim for over 60 years.

Similarly, Ingber's treatment of Zionist-Israeli "folk dance" lacks a detailed appreciation of "classic" Israeli dance in relation to 20th-century German dance, especially expressionist dance (Ausdruckstanz), and to the concept of the large-scale dance spectacle. She stresses only the Zionist discourse of "Return to the Land" and does not recognize proto-"Israeli" dance as in part the product of an internal German and German-Jewish cultural and political dynamic. With the exception of Oriental dancers like the Yemenite Sarah Levi Tanai and the Sephardic Yardena Cohen (the latter consciously rejecting German choreographic direction), most Palestinian Jewish choreographers were students of major German and Austrian teachers—though the majority of those teachers ultimately collaborated with the Nazis—and were often deeply involved in German artistic and ideological movements. Ingber's chapter on Nazi and Zionist views of the Jewish body is purely political; it does not treat the deeper issues of early 20th-century German aesthetic culture or the effect of group pageantry and pseudo-national traditions on modern choreography in both Germany and Palestine/Israel. Nor does Ingber refer to work on the invention of various national "traditions" in the Zionist Yishuv, such as that of Yael Zerubavel. But Giora Manor's 1986 article on the Inbal and Habimah dance companies is lucid and informative, and Dina Roginsky offers a sophisticated view of Israeli dance in "The Israeli Folk Dance Movement: Structural Changes and Cultural Meanings."

While Israeli dance receives substantial treatment here, a student of Jewish dance will be disappointed. We can be grateful for several well-informed and delightfully written articles and interviews, but the editorial direction does not display sufficient coherence or depth. "Jewish dance" as a basic feature of the historical and living culture of Jews still awaits serious scholarly treatment.

Walter Zev Feldman is a leading researcher in Ottoman Turkish and Jewish music, a performer on the East European Jewish cimbalom, and a practitioner and teacher of Ashkenazic dance. He is currently Professor of Music in New York University, Abu Dhabi (UAE).

¹Friedland, Lee Ellen, "Tantsn iz Leben: Dancing in Eastern European Jewish Culture," Dance Research Journal 17 (2), 1986., 77-80.

Comments are closed for this article.