Seeking Solomon

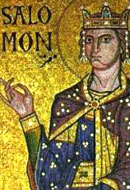

For traditionalists, the biography of King Solomon is enshrined in the Bible, in the narrative accounts in the books of Kings and Chronicles. The son of King David, who spent his career battling Israel's enemies, Solomon is depicted as ushering in an era of peace and prosperity. The Bible reports that he expanded Israel's territory, increased trade with Israel's neighbors, and oversaw numerous public works, including a magnificent temple in Jerusalem. According to Kings and Chronicles, Solomon was also blessed with unsurpassed wisdom, and Jewish tradition attributes the books of Proverbs, Kohelet (Ecclesiastes), and the Song of Songs to his hand.

Yet the Bible also relates (1 Kings 11:9-13) that Solomon took numerous foreign wives and concubines—a thousand in total—who led him to worship foreign gods and build shrines for their service. The punishment for Solomon's idolatry was the loss of half his kingdom: under the reign of his son Rehoboam, the northern tribes of Israel would secede and the kingdom would be rent in two. The dream of a unified Israel under the reign of a descendant of David, which remains in the prayers of Jews to this day, has never again come to pass in historical times.

Until several decades ago, the consensus among secular scholars was that the essential elements of the biblical accounts of Solomon's reign could be corroborated and illuminated by archeological findings and a judicious reading of the Bible. More recently, some prominent archeologists have argued that the architectural feats formerly ascribed to Solomon were in fact accomplished centuries later, calling into question whether the mighty king described in the Bible even existed. More recently still, this newer view has itself been shaken and, some say, undone by the dramatic findings of ongoing archeological projects in Jerusalem and elsewhere.

As debate over this issue rages, the very fact that such questions continue to be raised highlights how little unambiguous evidence there is for reconstructing the life and times of the man believed to be Israel's most powerful monarch. In the midst of this uncertainty, Steven Weitzman, a professor of Jewish culture and religion at Stanford, has produced an "unauthorized biography" of the king entitled Solomon: The Lure of Wisdom.

Weitzman paints a portrait of Solomon's life that is based neither on uncritical acceptance of the biblical account nor on historical reconstructions by secular scholars. Instead, he relies on an imaginative reading of the Bible supplemented by legends and lore promulgated by Jews, Christians, and Muslims over the centuries. He offers this portrait not as history but as a parable (Hebrew: mashal), and specifically as a meditation on the pursuit of wisdom and its consequences. Weitzman is fascinated not only by Solomon's legendary wisdom but also by his precipitous fall into idolatry. How is it, he asks, that the wisest of men could have succumbed to this gravest of follies, and what can this teach us about the nature of wisdom itself?

The biographical format of the book is somewhat forced. As the Bible says next to nothing of Solomon's childhood and adolescence, Weitzman endeavors to reconstruct them with the tools of Freudian analysis, but with results that even he concedes are not entirely convincing. By contrast, Solomon's rise to the throne, amply documented in the biblical narrative, is of limited interest to Weitzman and is covered in a single chapter. On Solomon's wisdom—the central topic comprising the bulk of Weitzman's book—the Bible again offers little specific information. As a result, the king's character seems more elusive with each succeeding chapter.

Though Solomon's figure remains mysterious, Weitzman's sources do allow him to introduce a vivid array of other historical characters: kings and messianic pretenders who viewed themselves as Solomon's heirs, explorers who pursued his vast wealth, philosophers who imagined him a master of the mysteries of the universe, and scientists who viewed him as an authority on the natural world. For Hellenistic interpreters, Solomon was a master of riddles; for the rabbis of the Talmud, he was variously a sage who brought the Torah to the masses and an exegete who fell prey to faulty interpretation of biblical law. What these readers of the Bible found in Solomon was often, unsurprisingly, a reflection of their own values, aspirations, and fears.

As for Weitzman's Solomon, he is a scholar whose thirst for knowledge is ultimately undercut by human fallibility. Weitzman is especially drawn to post-biblical versions of Solomon's story in which the king's cunning and insight lead to his downfall. In one talmudic legend, Solomon ignores the Torah's warning that marrying numerous women will lead a king into idolatry, wrongly believing that he can resist the temptation to sin. In another rabbinic tale, Solomon captures the demon Asmodeus, who later escapes, assumes Solomon's form, and replaces him on the throne. A medieval legend relates that Solomon lusted for the Queen of Sheba but was repulsed by her hairy legs—a difficulty he resolved by inventing a depilatory cream for the hirsute queen. Unfortunately, the offspring of their union was Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian emperor who ultimately destroyed the temple that Solomon had built.

Weitzman's reading of these narratives as critiques of Solomon's wisdom is somewhat at odds with the sources in which they appear. In context, the Talmud's account of Solomon's faulty exegesis serves not to portray the king as a particularly artful interpreter but to illustrate why the Torah does not typically justify the laws it promulgates. The story of Solomon and Asmodeus actually vindicates the king for his later crimes by attributing them to the demon. If there is a lesson in the medieval story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, the birth of Nebuchadnezzar would seem to be a consequence of Solomon's lust for the queen, not of his exceptional skills in cosmetology.

Still, in reading the sources as he does, Weitzman captures the longstanding ambivalence regarding the pursuit of knowledge that has troubled many a Western imagination and that continues to the present day. Despite well-founded fears of overreaching the bounds of human understanding—seen, for example, in contemporary debates over cloning—the drive to understand all that is in heaven and earth has never abated. This reverence for wisdom, both great and terrible wisdom, may indeed be what gives the figure of Solomon its timeless allure.

Eve Levavi Feinstein holds a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible from Harvard.

And Solomon's encounter with Asmodeus is a whale of a tale. Cast out of his kingdom and replaced by the shape-changing demon, the bedraggled Solomon makes his way back to the palace. Alas, none of his subjects recognize their majesty in the lowly stranger.

So the infinitely wise monarch devises an identity test. He asks that sand be sprinkled around the royal bedchamber. Now as everyone knows, a demon may change any part of his anatomy save for his feet. A demon has the feet of a chicken and that fact of Creation not even a prince among demons can alter.

Chicken tracks around the royal bed expose the demonic impostor and Solomon by his wisdom is restored to his rightful throne.

As a more mature reader, I learned that for character and drama and just plain good storytelling, none of the fables about Solomon come close to the original text.

Which is scarier, a chicken-footed demon in royal drag or the hot wife of a common mercenary soldier who trades up for a king by bathing naked under His Majesty's window and seducing him into dispatching her soldier husband to certain death and making her Queen?

Solomon is the realization of the prophet Samuel's warnings regarding the tyrannical nature of royals. King Saul was a Benjaminite country bumpkin who stumbled on a crown searching for his father's lost jackasses; King David was a charming and audacious usurper who spent most of his career in battle; Solomon is the Jews' first true royal, born in the palace and bred to rule.

In Solomon, the Jews finally meet the despot prophesied by Samuel when they willingly traded their freedom for servitude under a king. Solomon makes free with their daughters and reduces their sons to conscript labor unknown since Egyptian bondage. The profits of Solomon's wisdom accrue mainly to Solomon.

Why a modern Christian or Jew enjoying freedom and prosperity in a western democracy would yearn for the coming of a King-Messiah is a mystery.

That's pretty much Creed to many people, including Episcopalians. I am Episcopalian, and I sometimes ask myself and others with similar questions like yours David, would one be a member of a denomination and faith in good standing and not believe the Creeds or have faith in the Christ?

I think your question, David is one of freedom and prosperity, and what that may mean to those of us in the religious and Church going community. For me this is a little like the theme of the book, as I understand it, which is to debunk Solomon and his mythological and Biblical historic role as outlined in the Bible's Old Testament as a matter of allegory and teaching about God in history. I tend to both like the story, and find comfort in the message, which though perhaps not in archeological fact according to this scholar, still speaks to me in an illuminated and Holy way.

Peter Menkin

Mill Valley, CA USA

(north of San Francisco)

For Jews, the Hebrew word Messiah translates to an earthly redeemer descended from the tribe of Judah and the royal house of David. My argument was against royals. Life under Kind David included whips and scorpions. Solomon threatened his subjects with worse. And David and Solomon were merely kings. Imagine how intolerable life would be under a "king of kings" descended from these two.

Samuel, the Jewish leader second only to Moses was our first and greatest kingmaker. He is also among my personal heroes, a brilliant, courageous and implacable leader in a category with Caesar and Churchill. Samuel's hostility to royals made the Hebrew bible subversive literature to European princes, royal and Ecclesiastical.

The clamor for royalty that reduces Samuel to seeking the Lord’s advice and the Lord’s response—give the fools what they want—was much on the minds of the Founding Fathers--Christians, Deists and Freemasons—as they struggled to replace monarchy with a free and democratic republic. The system of governance they devised is far superior to rule by royals, anointed or otherwise.

Belief in the coming of a Messiah is a relatively latter day concept in Judaism. It expresses a yearning born of cruel oppression during the Second Temple period. Its adaption and transformation by the urban Gentiles masses into a Judeo-Hellenic theology undermined the Roman Empire and has brought incalculable suffering on the Jews for two thousand years.

The myriad blessings bestowed on and by the Patriarchs do not include a Messiah and an afterworld. Existential Evil, Heaven and Hell are not part of the Jewish belief system. Belief in a Messiah is arguably cultic and idolatrous. It should be jettisoned.

Again, Peter, my apologies. I meant no insult to your Episcopalian faith and creed. My question was aimed merely at Jews.

Comments are closed for this article.