Halakhah for Americans

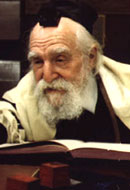

Asked in a 1975 New York Times interview how he had acquired his standing as America's most trusted authority in Jewish religious law (halakhah), Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (1895-1986) replied: ''If people see that one answer is good and another answer is good, gradually you will be accepted.''

This deceptively simple reply actually does help explain how a modest sage who first set foot on American soil over the age of forty, spent the last decades of his life on Manhattan's Lower East Side, and spoke Yiddish almost exclusively became the pre-eminent address for halakhic dilemmas that emerged specifically within the American context.

Born to a pedigreed rabbinic family in the Belarussian town of Uzda, Feinstein was educated in the yeshivas of greater Lithuania before accepting his first rabbinic post in 1916. Coming under increased pressure from the Soviet regime, he emigrated to the U.S. with his family in 1936 and soon accepted a position at a New York yeshiva, Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem. There he remained until his death exactly 25 years ago (March 23, 1986).

Both during his life and since his death, Feinstein has remained relatively unknown outside of the Orthodox community. There, however, his reputation is unassailable, based in part on his seven-volume commentary on the Talmud (1946) but mostly on his magnum opus, Igrot Moshe ("Epistles of Moses"): eight volumes of responses to queries from around the world addressing a dizzying variety of modern halakhic dilemmas.

As with any great jurist, the nature and scope of Feinstein's rulings defy neat categorization, though with the help of an ever-expanding secondary literature it is possible to identify a number of themes and trends.

For one thing, throughout, Feinstein differentiated Orthodoxy from other modern denominations, striving in particular to thicken the line between it and its nearest relative, Conservative Judaism. To that end, he elevated the requirement of mehitzah—the physical barrier between sexes in the synagogue—to the level of a biblical injunction; disqualified conversions and marriages solemnized by non-Orthodox rabbis; and forbade Orthodox rabbis from participating with non-Orthodox rabbis on communal or national boards. Although allowing some wiggle room in conditions of economic duress—for example, permitting Orthodox teachers to accept employment at Conservative institutions—his clear objective was to protect the traditional Jewish way of life from influences that in his view could lead to unbelief or non-observance.

Yet it would be a mistake to conclude that he was an extreme social conservative or Luddite; on the contrary, his goal was to enable that traditional way of life to function and indeed to flourish within 20th-century America. To that end, he steered an idiosyncratic path between accommodation and rejection. Nowhere is this more evident than in two consecutive responsa that deal with virtually identical (and, for Sabbath-observant Jews, equally problematic) modern technologies: microphones and hearing aids. In the first ruling, Feinstein writes that it is "clearly forbidden" to speak into a microphone on the Sabbath, enumerating four reasons for the prohibition. In the very next ruling, mitigating several of the arguments in the previous one, he authorizes those in need to use hearing aids on the Sabbath. Although he articulates a legal rationale, it is clear that this formal justification is constructed on an intuitive distinction between, on the one hand, tinkering with synagogue ritual and, on the other hand, accommodating and enabling the handicapped.

From this example alone, which could be multiplied a hundred-fold, one can identify a central feature of Feinstein's approach: what might be termed reluctant leniency. Although Jewish law has long recognized categories other than "forbidden" and "permitted," Feinstein tended to employ his particular yardstick in instances where leniency might be construed as a concession to the American milieu. Thus, he reluctantly permitted the consumption of government-certified milk (rather than only milk that had been processed under stringent Jewish supervision), the limited celebration of Thanksgiving, and riding in public transportation even when this would result in contact with members of the opposite sex.

In addition to practicing reluctant leniency in connection with the American environment, Feinstein strove to embrace disparate elements within the Orthodox community itself. On, for example, the internally divisive question of Zionism, he ruled that there was a mitzvah but no obligation to live in the land of Israel, thereby validating without mandating the Zionist impulse. When a group of men wished to split from a synagogue that displayed American and Israeli flags adjacent to the ark containing the Torah scrolls, he agreed that the display was frivolous and that symbols of the secular state of Israel had no place in a synagogue—but then instructed the group to remain anyway. In brief, if his desire with respect to non-Orthodox forms of Judaism was to create clear boundaries, within the Orthodox community it was to maintain communal cohesiveness.

All of these positions testify in part to the exigencies of Feinstein's historical moment. In postwar America, Orthodoxy was on the wane as Conservative Judaism enjoyed a radical upsurge, earning the allegiance of vast swaths of the emerging American-born, college-educated Jewish upper-middle class. Feinstein's form of Orthodoxy, at once rigid and lenient, outwardly secessionist and internally inclusive, was consciously designed to stand in the breach. In contrast to other writers of responsa, notably the encyclopedic Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, he tended to put forward his own often unprecedented and even unsupported readings both of social realities and of canonical texts, and these readings were often teleological; not a philosopher or an ideologue, he had a clear vision of what traditional Jewish life ought to look like, and he marshaled prodigiously erudite arguments in its support.

At today's distance, and especially in light of the dramatic shift in the respective fortunes of Orthodoxy and non-Orthodoxy, it has become increasingly possible to assess the success or failure of Feinstein's strategy. Within the Orthodox community itself, some of his rulings—on mehitzah and conversion standards, for example—have become institutionalized to the point where it is difficult to conceive of an American Orthodoxy without them. Others, notably on the halakhic definition of death—this and other life-and-death questions were another area of his expertise—have become the subject of controversy. Still other rulings, including, to a large extent, his strictures on dealings with non-Orthodox Jews, are respectfully ignored. Above all, the increased affluence and mobility of Orthodox American Jews, resulting in greater internal variegation, have led to an incipient reconsideration of the need to preserve Orthodox cohesiveness at all costs.

And yet, if the legacy of Feinstein's rulings is mixed, those rulings continue to carry greater weight than those of any other "American" halakhist. Among his successors—chiefly, two sons and one son-in-law—none has managed to command the wall-to-wall trust of the Orthodox community. Although America continues to have its share of Torah scholars, no one but Rabbi Moshe Feinstein was able to draw a subtle line between hearing aids and microphones—and get away with it.

Elli Fischer, who lives in Israel, is a writer and translator and blogs at adderabbi.blogspot.com.

From Samuel David Luzzatt's Prologomenon to a Grammar of the Hebrew Language:

"These [Rabbinic] Hebrew types, which we will call recenziori, that is, more recent, can be arranged into six classes:

A) Rabbinic recenziore Hebrew, used by the Rabbis and all of the writers of Tamudic material, Rashi, the authors of Tosafot, and generally the Ritualists (Poskim). The basis of this language is Mishnaic Hebrew, peppered, however with Talmudic Aramaic expressions. It makes almost no use of terms or phrases found in the Bible that are not in the Mishnah."

Luzzatto wrote before the revival of Hebrew as living language.

Be that as it may, Feinstein's inept Hebrew fits none of Luzzatto's categories.

S's posting is the best that Feinstein's defenders can come up with?

1. "His ruling of forbidding women from serving in the IDF is a blatant contradiction of the Talmud." And your source for that is where? Actually, if anything, there is an ban on women serving in the army. When that applies is an interesting question, but to say that it's a blatant contradiction is just foolish. (BTW, 99% of Orthodox rabbis believe the same. So Rabbi Feinstein was not unique here.)

2. Again, your source please?

3. As to your complaint about his Hebrew: First of all, there is no requirement for a scholar to write Hebrew like Agnon. His Hebrew is typical of responsa literature authored by people who did not converse in Hebrew, and it is eminently understandable by those who would like to understand it. Do you complain that Bialik didn't write responsa?

4. It's not Igorot but Igrot. Speaking of the pot calling the kettle black...

5. I notice that despite your apparent affinity for the Hebrew language, the revival of which was generally part and parcel of the Zionist movement, you live in Maryland and not here. Hmmm...

The only article that I used extensively that is not linked here is Pinchas Peli's obituary (Hebrew).

Then you should have acknowledged Peli in your post. Per Rakeffet's article, I suggest that the discerning reader examine both and decide for himself.

R. Fischer, is this the obituary by Pinchas Peli?

http://aleph.nli.org.il:80/F/?func=direct&doc_number=000085205&local_base=RMB01

Any chance you can post a link to it? Thanks for your article. I only discovered it a few days ago, and then comments started appearing again.

Comments are closed for this article.

His ruling of forbidding women from serving in the IDF is a blatant contradiction of the Talmud, making Feinstein more REFORM than Orthodox.

Even his son-in-law, M.D. Tendler shlita, admits that Feinstein should not have said that "all Conservative rabbis are atheists"- an outright lie.

Finally, I defy anyone to find for me a single full-length sentence in Igorot Moshe that is written in grammatically and syntactically correct Hebrew!