Needing Jeremiah

One of the most significant accomplishments of the Zionist project was to re-vitalize the Bible as a Jewish national document. Or, if not the Bible as a whole, at least parts of the Bible. The early Zionists were attracted in particular to those books, like Joshua and Isaiah, which appealed to the dream of return and political restoration. One biblical book that most definitely didn't fire the Zionist imagination was the book of Jeremiah.

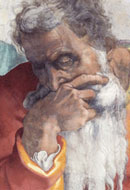

The prophet Jeremiah lived in the period leading up to the destruction of the first Temple (586 B.C.E.), and while he began his career dreaming about the reunification of the kingdoms of Israel and Judea—the two had split after King Solomon's son Rehavam came to power—he ended by prophesying destruction and, according to Jewish tradition, composing in its aftermath the great howl of grief that is the book of Lamentations. Concluding that the nation in its moral degeneration had moved beyond the point of no return, Jeremiah had also counseled submission to the rule of Babylon, thereby renouncing Jewish political sovereignty. For this he was regarded as a traitor by some of the patriots of his time and, closer to our own time, as a repudiator of one of the principal elements of the Zionist vision.

To this day, indeed, Israeli high-school students are exposed to only a very small portion of the book of Jeremiah, while to most Israelis the story of the prophet's life remains unknown. This is a situation that Rabbi Benjamn Lau, a leading figure of the religious-Zionist camp, has set out to change in Jeremiah, a Hebrew-language book that is soon to be translated into English. In redeeming the prophet from the margins, Lau both retells the book's "plot" and enters a striking claim for Jeremiah's relevance to contemporary Israeli concerns.

Two obstacles stand in Lau's way. The first is that the text of Jeremiah is choppy and the story doesn't always proceed chronologically. The second is that, absent a prior familiarity with the history narrated in the biblical books of Kings and Chronicles, the reader will have little sense of the pertinent context. Lau has overcome both of these difficulties by rearranging the book's narrative according to its proper chronology and supplying the historical-political context, occasionally adding insights culled from academic historians and archeologists.

The precision of Lau's retelling can be contested, but the broad strokes aren't in dispute. During Jeremiah's lifetime, the kings of Judea, from Josiah to Jehoiakim to Zedekiah, all failed to recognize the limits of their power and became unnecessarily embroiled in external adventures, while the nation as a whole foolishly placed its faith in foreign alliances and the succoring presence of the Temple in its midst. As against this twin dependence on power politics and the Temple, Jeremiah insistently and repeatedly proclaimed "a necessary connection between social justice and national existence." True Jewish patriots, he declared, were moved by a sense of justice and sympathy for the weak, by "the cause of the poor and needy. . . . Was not this to know Me? said the Lord" (22:16).

From this it is easy enough to discern where Lau locates Jeremiah's contemporary relevance. The state of Israel is weighed down today by serious social problems, from the status of foreign workers to forced prostitution—problems often pushed aside by the need to focus on the country's strategic situation. Among some, there is also a kind of insouciance about the country's supposed indestructibility, an attitude no less superstitious than the ancient dependence on the Temple. As Lau notes toward the end of his book:

There are still false prophets in Jerusalem proclaiming, "We have a tradition from our forefathers that the third commonwealth [i.e., the state] won't be destroyed." Their function is to put us to sleep and make us forget our weighty responsibility: to be deserving of this house.

Lau's Jeremiah is thus a rabbi's warning against national and/or religious self-confidence divorced from a social conscience and the commitment to moral excellence. In one sense, it may be said (though Lau doesn't say it) that his warning goes to the heart of the modern project itself, and to the war waged by hard-boiled thinkers like Machiavelli and Hobbes to emancipate politics from theology. Reversing the trajectory, Lau's Jeremiah reconnects the two by implying that their disconnection was what doomed the Jewish state in the first place. In this sense, his warning is pertinent to contemporary situations, and dilemmas, well beyond the state of Israel.

More specifically, though, Jeremiah constitutes a challenge to Zionist and religious-Zionist pieties. Among secular Israelis, interest in the Bible has waned with the passing of the heroic phase of the Zionist revolution. Meanwhile, within the religious-Zionist camp, a battle has been waged between those who would read the Bible "at eye-level"—meaning, on its own terms and without the mediating presence of traditional commentaries, and those who consider it forbidden to read the text without the aid of those commentaries.

Lau comes down firmly on the side of the former camp: his Jeremiah is an "eye-level" reading that by and large bypasses rabbinic interpretations. It thus remains faithful in its own way to the Zionist project of reclaiming the Bible through the recovery of the plain, surface sense of the text (especially, for the early Zionists, its political sense). By proceeding in this way, he has indeed succeeded in reanimating the text for a new generation. No less importantly, he has also succeeded in demonstrating the enduring power of the Bible's most tragic prophet, and—here is where his challenge to certain of today's pieties comes in—in bringing front and center that prophet's core, clarion message: the hazards of hubris.

Rabbi Filber and other students of Rabbi Zvi Yehudah Kook succeeded in creating a youth culture which was both functional and self-confident. This was reinforced by an emerging secure ideological environment, political changes in Israeli society and frequent reassurance offered by the rabbis of the school. These young rabbis offered gentle paternal-like support to youth that fostered a self-assurance that had a holding power on the devout among them despite Haredi scepticism regarding the authenticy and depth of its religious doctrine and questions about the ramifications of its messianism by more cautious Mizrahi rabbis such as Rabbi J.B. Soloveitchik, outspoken figures such as Yeshaya Leibovitz and center-to-left secular Zionists. The questions raised were either ignored or derided as “galuti.” They needed no answer; the answer was in the success of the project.

It is no wonder that the sector of religious Zionism that has been termed by Rav Amital as “the aggressive and screaming faction” (alima vetza’akanit) was stunned at the withdrawal from Sinai, the Oslo process and the disengagement from Gaza. These were not supposed to happen (“hayo lo tihyeh”). But aside from the aggressive and screaming hubris, there is also a gentle, self-congratulatory type of arrogance that arises when one is so self-assured that one’s own construction of reality becomes the only possible one and questions need no answers. It seems to me that that Rabbi Filber has recently and unwittingly demonstrated what I mean by this in a critique that he wrote of Rabbi Benny Lau’s book (in Hebrew at http://www.kipa.co.il/jew/show.asp?id=40721). I am certain, however, that readers who are of like mind with Rabbi Filber will read the essay in an altogether different light that I have. Nevertheless, as doctrine drifts further from reality, crisis results.

Half of Israel still lives in exile. Moreover, Jews in exile for thousands of years did not neglect the "word of

God" and they still suffered untold miseries and death.

What about the Germans or the Japanese or the Russians or Iranians, are they to be given a pass?

Are all peoples to suffer exile if they neglect "the word of God," or only the Jewish people?

Where do you come off preaching so glibly about "God's word?"

Rabbi Lau's first work to appear in English just came out! It is the first volume of a 3-volume series entitled The Sages: Character, Context & Creativity. Available on www.korenpub.com, Amazon and at Jewish bookstores everywhere.

But R. Filber is essentially correct - even without adopting the theology of Mercaz Harav - who says that Benny Lau is not the "false prophet"? Just b/c what he writes appeals to elitist sensibilites doesn't make it rational. Look at the Oslo Accrods - there was nothing rational about that!!

But, of course, what that means to some is that it doesn't really matter at all if each one of us has a conscience, only that the gov't is socialist.

And therein is the problem. A socialist gov't with leaders who wouldn't give a personal dime to charity if their lives depended on it. We know all about how that works in the US.

And since when is simply believing the Bible "preaching"?

For example, “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your Country” is provocative. So is “The Jews should get the hell out of Palestine and go back to Poland or Germany.”

While some statements provoke actions, others provoke contemplation and then argument, in both the neutral and common usage of that word.

When you come right down to it, most of what is said or written is provocative. The nature of the response is dependent on context. “Nice day, isn’t it,” can lead to a brawl in certain circumstances.

The thing I like most about Aryeh’s articles, beyond my pride, is what I learn from them. The thing I like second most is the broadness of the responses that they provoke. Beyond instructing, the articles make people think. And beyond that, they provoke a solidarity of purpose among Israelis to work toward bringing together Israel’s future with Israel’s raison d’etre.

Julian Tepper

Placitas, NM

David: thank you for your very interesting account and analysis of the youthful spirit and historical conditions that, once upon a time, drove the impulse of messianic religious Zionism (MRZ).

I don't think R' Benny Lau is aiming to fashion an alternative to MRZ, or articulating the classic R' Reines voice of Mizrachi Zionism. His view is broadly mamlachti, a kind of republican civic nationalism. In delineating his view he does take aim at MRZ, for sure, but I think his main aim is to accentuate the social aspects of the Jewish tradition and to articulate a kind of religious-cultural Zionism. If I understand correctly, his hope is that this religious-cultural Zionism will become an integral part of Israel's political, social, and cultural conversation. If some disillusioned religious national youth are attracted, all the better.

Yo: how to translate a social conscience into social policy is an important question. Hopefully Jewish-Israeli thinkers who understand both economics and Israeli society and are well-versed in the economic aspects of the Jewish tradition will thoughtfully tackle the question. Some interesting things have been written. If you read Hebrew, see for starters the pamphlet:

צדק חברתי ומדיניות כלכלית במדינה יהודי, אוניברסיטת בר אילן, שבט תשס"ד.

Rav Benny Lau's view is not a return to classical mizrachi zionism. if anything it is a return to modern-orthodox non -(or even anti-) zionism - such as e.g. Torah Im Derech Eretz austriit Jewry in Germany.

In the critiques of this book from this past weekend's Makor Rishon, one of the writers stated explicitly that "one must negate the idea of cathartic exile as a legitimate Jewish view for the modern era - whether it is proposed by someone wearing a shtreimel or someone wearing a knitted kipah."

A more important question that pertains to our lives is what to make of the statement that there will be no third hurban or galut. This is quoted in religious Zionist circles in various forms as having been said by Rav Yitzchak Herzog. It becomes problematic when these quotes and statements by Rav AI Kook are presented quite literally as prophecies to be relied upon to support specific political agendas. In circles with these attitudes, it is rarely debated whether the final redemption may take another few hundred years, whether unwise decisions could result in the unnecessary loss of lives and wealth, and whether such decisions should be the result of ordinary political debate and not theological rulings. Similarly, negating whether an idea is a legitimate Jewish view for any era, attaching labels presumed to have negative connotations (such as 'defeatist'), etc. serve no construtive purpose, but rather serve to end discussion of ideas that have merit but may be uncomfortable.

Comments are closed for this article.

The article neglected to mention, however, the very relevant penalty for ignoring God's voice -- exile.