The Daily Page: A “Siyum”-posium

UPDATE: New posts as of 8/3/12, 1:11 a.m.

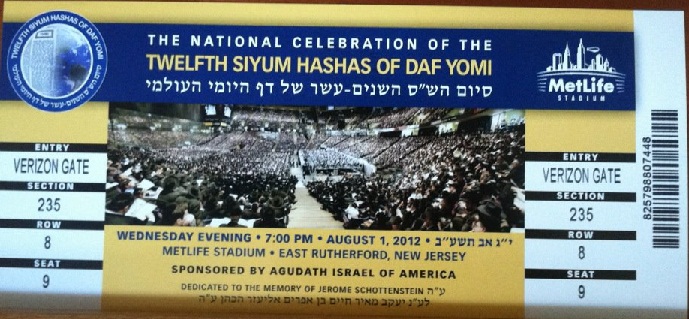

Last night some 90,000 people gathered at the MetLife stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey for a ceremony celebrating the twelfth completion of the daily reading of the Talmud (Siyum ha-Shas). The event followed similar ceremonies, in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Bnei Brak, London, Melbourne, and other cities and communities around the world, in which thousands more participated in person or via closed-circuit TV.

These events honor the conclusion and re-commencement of a seven-and-a-half-year cycle in which people—individually, with partners, or in groups—learn a folio page (two facing pages) of the Babylonian Talmud each day in a tradition known as daf yomi, “a page a day.”

The tradition was established by Rabbi Meir Shapiro, the Hasidic rebbe of Lublin. Rabbi Shapiro proposed the idea to the Agudath Israel convention in Vienna in August, 1923, and the enterprise was launched with much fanfare the following Rosh Hashanah. Over the course of the twelve cycles completed thus far, the number of learners has burgeoned to many tens of thousands around the world.

To mark the occasion, Jewish Ideas Daily invited several prominent thinkers to reflect on the phenomenon of daf yomi and their own engagement with the practice. Stay tuned as we will periodically publish excerpts from their responses; a free downloadable e-book containing the full essays will be available soon. —The Editors

Photo by Michael Carasik.

_____________

Talmud Transports Me

By Saul J. Berman

The study of Talmud transports me outside myself into different worlds: into the world of the farmer struggling to produce crops and to share fairly; into God's world of Holy Time; into the world of complex family formation, interactions and conflicts; into the world of the ethical challenges of business transactions, the achievement of justice and criminal punishment; and into the world of the ancient Temple of Jerusalem with its special purity rules and its regulations of the offerings of self and property in divine worship. To this day my wife tells me that she can tell when I haven't cracked a Gemara for a few days, because I become grumpy and morose, uncommunicative and generally miserable.

Almost thirty years ago, as Rabbi at New York’s Lincoln Square Synagogue, I tried to keep up with the cycle of daf yomi for six years, and taught it once or twice a week. Still, this was only a partial endeavor: not every day, not every daf, and often resentful of other impingements and commitments. I even went to the Siyum Ha-Shas in Madison Square Garden in 1989, and after hours of prosaic speeches, experienced a spiritual high as over 20,000 voices cried out the praise of God at the start of evening prayers: Baruch Hashem hamevorakh l’olam va'ed! May God's Name be blessed forever and ever! It was not the voices of Torah giants or of rabbis that were transformative; it was the collective voice of the people—the people who discovered the voice of God through Talmud study.

Perhaps I'll try it again in the cycle about to begin.

Rabbi Saul J. Berman is Associate Professor of Jewish Studies at Stern College of Yeshiva University and Adjunct Professor at Columbia University School of Law, where he teaches seminars in Jewish Law.

_____________

The Zionists of Boro Park

By Yehudah Mirsky

The second recorded daf yomi class on American shores was inaugurated in 1940, and taught for decades by my grandfather, Samuel Mirsky, longtime rabbi of the Young Israel of Boro Park, professor at Yeshiva University, and a then-leading figure in religious Zionism. Hard to believe, but Boro Park was once a stronghold of Hebraists and Zionists, secular and religious both. As my grandfather wrote in a booklet published by the circle in 1942, while he'd contemplated turning his weekly Talmud class into a daf yomi, it was precisely his participation in the fateful Zionist Congress of 1939 that gave him the impetus to launch, out of a sense of the “duty to maintain the supremacy of the book, while the sword reigned supreme in the world.” In a volume marking the 20th anniversary of the circle, he wrote that he and the others were driven by what was for them a classic religious Zionist motivation: to unify as much of the entire Jewish people as possible, through the study of classic texts.

Familial boosterism aside, there is a larger point here—the successes of American Jewish life are the products of extraordinary efforts by a host of people, of varying and differing, sometimes conflicting beliefs and ideologies, many now forgotten. Their descendants, physical and spiritual, are still building, one by one, each in their circles, today.

Yehudah Mirsky served in the State Department's human rights bureau in the Clinton Administration and moved to Israel in 2002. He is active in Yerushalmim.org, and his biography of Rav Kook is forthcoming from Yale University Press. To read more about Rabbi Samuel Mirsky’s daf yomi circle, see pp. 37-38 of Viewpoint.

_____________

Gains and Losses

By Shlomo Zuckier

The success of daf yomi points to some very positive developments, primarily the explosion of Torah study in post-World War II America. The current reality, where large sectors of the Orthodox population take for granted that they will set aside anywhere from one to ten years studying traditional Jewish texts is astounding, especially when considered against the dire predictions for American Orthodoxy in the 1960s.

Notwithstanding the positive gains, daf yomi also reflects some less than salutary trends. The need for the “learner” to perpetually have a clear, quantified goal betrays the influence of a results-oriented American corporate culture that stands at odds with the traditional ideal of studying Torah for its own sake (lishmah). Moreover, daf yomi is necessarily a cursory study of the Talmud, as it is impossible to come away with a grasp of the range of medieval interpretations, contemporary halakhic applications, or jurisprudential issues at hand, in one short hour. It is a deeply ironic turn that the followers of Rabbi Aharon Kotler, who championed Torah study at the deepest level and eschewed superficial engagement, now preside over the dais at the siyum. We have many reasons to celebrate these accomplishments, but also must reflect upon what has been lost in the process.

Shlomo Zuckier is a Tikvah Fellow and an editorial assistant for Tradition magazine. He is a rabbinical student and Wexner Fellow at Yeshiva University.

_____________

Two Thousand, Seven Hundred and Eleven Days in a Row

By Jacob J. Schacter

What is the most fundamental verse in the Torah, the anchor upon which everything rests? Ben Zoma suggested the well known Shema Yisrael: “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One” (Deuteronomy 6:4). In his view, the basic philosophical principles of Judaism found in this verse—the existence and unity of God—are most important. Ben Nanas pointed to the famous “Thou shalt love thy fellow as thyself” (Leviticus 19:18). For him, sound, sensitive interpersonal relations take priority. But there is a third proposal—one that on the surface seems much less significant than either of the other two. Shimon ben Pazi offered, “The one lamb you shall make in the morning . . . and the second lamb you shall make in the afternoon” (Numbers 28:4, 8; see R’ Jacob b. Solomon ibn Habib, Eyn Yaakov, introduction, end). How could this verse possibly be considered the most important in the Torah?

Shimon ben Pazi highlights a fundamental principle. Yes, philosophical knowledge and sensitivity in interpersonal relationships are vitally significant. But perhaps even more significant is the constant discipline and focus necessary for meaningful Jewish life, “in the morning” and “in the afternoon,” every morning and every afternoon, every day, always.

Like the twice-daily Temple sacrifice that serves as the context for these verses, the study of daf yomi requires an ongoing, consistent commitment, day in and day out, every single day—weekday, Shabbat, holiday, fast day—for two thousand, seven hundred and eleven days in a row.

On August 2 one cycle ends. On August 3 another cycle begins. And so may it be, forever.

Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter is University Professor of Jewish History and Jewish Thought and Senior Scholar at the Center for the Jewish Future at Yeshiva University.

_____________

Soldiering On

By Alon Shalev

One of the most trying challenges for religious soldiers, a challenge which has greater implication for the young soldier than one might think, is that of keeping up his or her Torah learning while in service. This is particularly true for the former yeshiva/midrasha graduates who, with conscription, are left with a void in their lives as they set aside the study of Torah for the sake of the greater good. At that point, daily learning sessions can become a spiritual lifesaver.

Many find refuge in daily study of the Hafetz Hayim, perhaps Hok L'yisrael. Some, however, refuse to give up their beloved daf. On many large bases that employ a rabbi-chaplain you can find a seder daf yomi between services, mainly serving non-combat personnel whose schedules allow for it. But even within the ranks of the combat soldiers there are those who, in an act of great dedication, steal time between guard duty and patrols to go through a daf, alone or with a fellow soldier, and, if their learning is interrupted, spend the precious little leave time they get catching up with the daf yomi schedule.

Major Roi Klein z”l, who became a national hero during the second Lebanon War when he jumped on a grenade hurled at his soldiers, was such a man. Even under the weight of his responsibilities as leader and commander, he never gave up on learning Torah through the daf yomi. With the daf he managed to embody the religious soldier's great aspiration of combining safra and sayfa—the book and the sword, fulfilling the noble duty of protecting one's people while still living as a ben Torah.

Alon Shalev, a fellow at the Tikvah Fund, served in the IDF from 2003 to 2007.

_____________

The Founder and the Foundation Stone

By Yoel Finkelman

The interwar years were dramatic times for Orthodox Jewry in Poland. The country was modernizing, rapid secularization was undermining traditional Jewish life, and Torah study was on the decline. Rabbi Meir Shapiro (1887-1933) was a major player in Orthodox responses to these challenges, and his innovations have stood the test of time.

Shapiro founded a revolutionary institution: Yeshivas Hakhmei Lublin, a pioneer among Hasidic yeshivas. The Hasidic world had initially rebelled against the yeshiva-centered rabbinic elite, but Shapiro understood that the two movements needed to move closer together and that Hasidim needed a richer connection to advanced Torah study to survive. His aim was to bring honor and respectability to yeshiva study in an age when Torah students were ridiculed as backwards. In place of the asceticism of old-style yeshivas, Shapiro built a state-of-the-art facility. Instead of students’ lodging in local spare bedrooms, Yeshivas Hakhmei Lublin provided them with a modern dormitory and a dining room. Today, virtually all major yeshivas have followed suit.

But Shapiro’s innovations didn’t end there. He wanted to unite all observant Jewry around Torah study, and suggested to the Agudath Israel convention in 1923 that Jews worldwide study one page of Talmud each day at the same pace. Agudath Israel took the project under its wing, and the first cycle of daf yomi began on Rosh Hashanah that year. The program now represents the largest Torah-study program in the history of the Jewish people. How many Jewish leaders can claim such long-standing successes?

Dr. Yoel Finkelman lives with his wife and five children in Beit Shemesh, Israel. He is the author of Strictly Kosher Reading: Popular Literature and the Condition of Contemporary Orthodoxy.

_____________

A Wedding and a Funeral

By Michael Carasik

I have to admit I missed the siyum. Not the gathering at MetLife Stadium, which was filled with Jews who, like me, were celebrating their completion of the daf yomi cycle. What I missed was the actual siyum, the learning of the last few words of Tractate Niddah. I thought the speaker had just lapsed back into Yiddish. (He was not the first, and would not be the last, to do so.) The penny finally dropped when I realized he was in the middle of the Hadran, the recitation in which learners promise to return to the tractate for more learning in the future.

And so the celebration began. The music and the dancing were what you'd experience at a Haredi wedding. The circles that moved were down on the field; in the second deck we couldn't do much more than sway back and forth. (Women, to judge by the curtains that were drawn during the minhah prayer that began the event, were in the third deck, in the end zones.)

There's another way in which this was like a wedding. As one of the speakers explained, completing the Talmud just means that you've laid a solid foundation for the marriage: the life of learning that still lies ahead of you.

But the evening had the aspect of a funeral as well. As the speakers presented it, there are two reasons to learn daf yomi, and one of them is to frustrate Adolf Hitler (“yimah shemoy ve-zichroy,” may his name and remembrance be blotted out). The more positive way to frame this is to say that we are learning on behalf of the six million who were prevented from doing so. That's what 16,000 "masmidei ha-siyum" did, school kids who learned innumerable lines of Talmud to be applied to the heavenly credit of the slaughtered children.

The other reason they put forth is that one learns daf yomi to be part of Klal Yisrael, the Jewish commonwealth. No matter whether you were wearing a black hat, a shtreimel, a knitted kippah, or a baseball cap, everyone was learning the identical daf. When enough Jews get on the same page, God will surely bring the Messiah—"speedily and in our days."

I was wearing a straw hat, and felt both a part of and apart from this celebration. My moment came in an unexpected way—in an e-mail that came through around 9:30 p.m., from a student who did not know that I was at the siyum too, thanking me for our learning together.

For me, that is reward enough for now.

Michael Carasik is the creator of The Commentators' Bible and of the Torah Talk podcast. He teaches at the University of Pennsylvania.

_____________

Every Single Rashi

By Tzvi H. Weinreb

I received special blessings when I began teaching daf yomi from both Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky zt"l and the Klausenburger Rebbe zt"l. They both urged me to be sure to teach every single one of Rashi’s commentaries on every page, and neither would give me a blessing until I gave them my word that I would do so.

Rav Yaakov said, "if the [students] come away from the [class] appreciating Rashi's greatness, that itself will be a major accomplishment." The Rebbe went further and said that only when one learns Talmud with Rashi can one be sure one is learning true Torah.

Sadly, I never had the opportunity to ask either of these great sages what I was to do for those tractates for which there is no commentary by Rashi (such as Nedarim, Nazir, and Shekalim). I consulted Rav Yaakov Moshe Kulevsky zt"l, then the head of Ner Israel Rabbinical College of Baltimore, who advised me to extract basic discussion points from the primary commentators on those tractates and "build your own Rashi."

Often, when I hear classes nowadays, I find that the lecturer quotes all sorts of sources, frequently complicating rather than clarifying the daf. What my teachers taught me is "the simpler the better": that the important thing is to understand the "shakla v'tarya," the give and take, of the great text itself.

_____________

On Love and Commitment

By Devora Steinmetz

Our sages compared learning Torah to the love between two people. If learning Torah is a love affair, then learning daf yomi is a marriage.

Much of the time it is a joy. But sometimes it’s not, and that is exactly the point. Learning daf yomi is akin to sustaining a loving relationship: It demands that you give your time to the other and open yourself generously to hearing what the other has to say. If sometimes what it says makes you mad, you know that you will still be there the next day to continue the conversation. And if some days you really don't want to bother, you know that you have committed to be present nevertheless.

Daf yomi, like prayer, is a service. Yet it is different from the daily ritual of prayer—it is focused on hearing the word of the other rather than pouring out one's own words. Learning daf yomi provides the opportunity to set aside a time each day to re-establish your commitment to the mundane, sometimes exciting, at times frustrating, and always deeply loving relationship between yourself and the sacred word.

Devora Steinmetz has taught Talmud and rabbinics at the Jewish Theological Seminary, Havruta: A Beit Midrash at Hebrew University, Drisha Institute, and Yeshivat Hadar. Steinmetz serves as an educational consultant for the Mandel Foundation and is spending this year as visiting faculty at the Mandel Leadership Institute in Jerusalem.

_____________

How Talmud Came to Displace Bible

By Moshe Sokolow

The contemporary preoccupation with Talmud has rendered the phrase talmud torah (literally, Torah study, referring principally to the Bible), almost an oxymoron. Up to the early modern period, knowledge of Bible was generally regarded as an indispensable tile in the mosaic of a learned Jew. Until the last century it was invariably the great talmudists and halakhists who were themselves the biblical exegetes. (Rashi, Nahmanides, and the Gaon of Vilna come readily to mind.) In the modern era, however, and the 20th century in particular, the scope of traditional erudition has contracted to include little more than the proverbial “four cubits” of halakhah and very few rabbinic giants have devoted themselves to the explication of the Bible. Indeed, it is questionable whether—with significant exceptions—they would even acknowledge a thorough knowledge of Bible as a desideratum, let alone a prerequisite, for recognition as a talmid hakham (scholar).

The current proliferation of sermonic anthologies on the weekly Torah portion (parashat ha-shavua), some by outstanding talmudic scholars, should not be mistaken for a renewed interest in Bible, for nearly all betray the telltale mark of amateurism: the lack of system and technique. When asked to assess the highly eclectic ArtScroll Torah commentary, Nehama Leibowitz (1905-1997) was wont to say that it was fatuous to compare Rashi, who invested a lifetime in developing a method of Torah study, to the Czypiznocker Rebbe (a figment of her dexterous literary imagination), who once revealed an insight into Torah during shalashudos (the Shabbat afternoon meal).

Perhaps, in time, we will witness a return to a status quo ante described by the Midrash:

Just as a bride is bedecked with 24 jewels and if even a single one is missing she is naught, so must a scholar be familiar with all 24 [biblical] books and if even a single one is missing he is naught.

Moshe Sokolow is professor of Jewish education at the Azrieli Graduate School of Yeshiva University.

_____________

Medium and Message for Modern Orthodoxy

By Mark Gottlieb

A too self-satisfied student of Rav Yisrael Salanter, the great 19th-century Lithuanian Mussar master, eagerly bragged to his rebbe that he had been through the Talmud seven times. Rav Salanter was reported to have replied, in his morally perspicuous way, “That is well and good, but how many times has the Talmud been through you?”

Much of the discussion of the omnipresence of Talmud in the traditional yeshiva high school curriculum has centered around the question of “relevance,” with the side of traditional Brisker lomdus [analytical study] squaring off against the newer schools of applied, contextualized, values-driven interpretation and teaching. Daf yomi defers that difficult debate, and powers on simply by virtue of the “givenness” of the text and the value of daily study. But if Talmud is to be more than an internally coherent yet existentially empty study for our students, much more needs to be said and done. Rabbi Shimon Gerson Rosenberg (Shagar) z”l and others in his wake have begun probing the Talmud for ideas for the contemporary social, political, and cultural life of the Jewish people—in short, a worldview—but modern Orthodoxy in North America must now play catch-up.

Rabbi Mark Gottlieb is Senior Director at the Tikvah Fund. Prior to joining Tikvah, Rabbi Gottlieb was Head of School at Yeshiva University High School for Boys and Principal at the Maimonides School (Brookline, MA).

_____________

Bruria and Women’s Illiteracy

By Viva Hammer

I am a semi-literate Jew. Vowelized Hebrew I manage, but unvowelized Hebrew I grope through slowly and painfully. Jewish civilization is embodied in unvowelized Hebrew texts and I can access none of it. Not only do I miss a page of Talmud daily; I couldn’t manage one such page in a lifetime. And yet I lead a life immersed in Jewishness. When I became betrothed to a scholar, the son and grandson of scholars, no one considered my Torah learning in determining my suitability as a wife. Jewish illiteracy has not hampered my progress in any sphere.

Our firstborn was a girl; we named her Bruria. In the pantheon of scholars that animate the Talmud, there is one female peer: Bruria. The wife and daughter of talmudic giants, she is held out as the embodiment of brilliance. In one legend a man sets himself an ambitious goal in learning, but is chided that his target would be impossible even for Bruria, who learned three hundred laws from three hundred teachers in one day!

Text is the core of Jewish civilization. If we want our daughters to know whence they have come, they need to be literate in all manner of Jewish text. And more, if they are to be part of what is handed to future generations, they must create Jewish text. The literacy of which I speak does not come from reading a sourcebook of sheets torn out and repackaged from a hundred books, the singular method used to educate religious girls. A person can live a full and meaningful Jewish life even if, like me, she is semi-literate. But such a person cannot participate in the great dialogue of Jewish civilization, cannot be a Bruria.

So where could we educate our Bruria to learn the daily page of Talmud and then to teach, to judge, to innovate in the tradition of her namesake? The best place we could find was a sweet high school where a manicured curriculum was ladled out by well-meaning instructors. But Bruria screwed up her nose at it and went to college instead. There she could learn three hundred laws from three hundred teachers in one day. But not Jewish laws: no school would teach her those.

And so our Bruria will continue in the great tradition of women’s semi-literacy in Jewish texts. How could she break it? And why?

Viva Hammer is a partner in KPMG's Washington National Tax and a Research Associate at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Brandeis University. She is the Women's Whispers columnist at the Jerusalem Post and has written for the Washingtonian, the Forward, Lilith, and several literary magazines. Viva is a homeschooling mother and is writing a book about family size in the Jewish world, called Choosing Children. You can find out more of Viva's activities at www.vivahammer.com and can reach her at vhammer@brandeis.edu.

_____________

How Three Days of Daf Yomi Changed My Life

By David Glasner

In August 1976 I arrived in Milwaukee to teach economics at Marquette University. After attending Rabbi David Shapiro’s weekly Talmud class at Congregation Anshe S’fard for a few months, I got a call from one of the other regulars, asking if I might be interested in starting a daf yomi class with Rabbi Shapiro instead. I heartily agreed. The Talmud class had usually drawn 8 to 10 people, and at least that many, probably more, came to the first daf yomi class. Even in the ‘70s, daf yomi had a certain drawing power.

The daf yomi was then in the middle of Tractate Rosh Hashanah, and on that first night, after two hours (and a bit of grumbling), we almost—but not quite—finished the daf. The next night, after another two hours of study, we not only didn’t get caught up, we fell further behind. Once Rabbi Shapiro found something that he didn’t quite understand, or if someone raised an interesting question, he would not let go without looking through all the relevant sources in search of an answer. On the third night, after another two hours, we had fallen hopelessly behind schedule. At that point, about half of the people gave up, and the other half, including me, stayed with it—but dropped the pretense that it was a daf yomi class. For the next four and a half years, the class continued five or six nights a week. In my entire life, I never studied the Talmud in as much depth or with as much enthusiasm and enjoyment as I did those years with Rabbi Shapiro. Indeed, in my entire professional career, despite having had two Nobel Prize-winning teachers, I never had a more rewarding intellectual experience. So although there is undoubtedly a lot to be said for staying on a schedule and learning the daf every day, there is also something to be said about learning just for its own sake without regard to an artificial schedule—just learning until you are satisfied that you have really understood the Gemara you have set out to study.

David Glasner is an economist in the Washington, D.C. area and writes about economics on his blog uneasymoney.com.

_____________

Levites and Learners

By Aryeh Tepper

The great Andalusian Jewish poet, Yehuda Halevi (ca. 1075-1141), wrote that the Torah, understood in its broadest sense, includes all wisdom, including music (see Kuzari 2, 64). In biblical times, the job of learning and performing music was given to the noblest members of the nation, the Levites, who were sustained through public funds (tithes) so that they could be free to concentrate on making the music that accompanied the Temple service and gave vitality to the Jewish people. And today? The yeshiva world, ground zero for single-minded Gemara study, has arrogated to itself the title of the tribe of Levi, and the masses of Jews learning daf yomi have followed their lead by conferring upon Talmud study a cosmic value. What would King David, the poet-warrior, the sweet singer of Israel, say about an army of servants to the texts—themselves outfitted like black ink marks on a white page—"O, how the mighty have fallen . . . "

Aryeh Tepper is a visiting scholar with the Tikvah Fellowship, and a regular contributor to Jewish Ideas Daily. His book, Theories of Progress in Leo Strauss' Later Writings on Maimonides, will be published by SUNY Press in 2013. He attended a number of traditional yeshivot in Israel and he loves Talmud—just not as the beginning and end of Jewish life.

_____________

Mainstreaming Talmud

By Marc B. Shapiro

Although it is a sore spot for modern Orthodox intellectuals, the popularity of the ArtScroll Talmud has been an engine of daf yomi study, allowing even beginners to grasp the most difficult talmudic texts. I am not exaggerating when I say that there are people now completing the study of the entire Talmud who can barely read a Hebrew or Aramaic sentence, and the thanks (or blame, depending on your perspective) for this must go entirely to ArtScroll. At the same time, there is hardly a daf yomi lecturer who does not look at what ArtScroll has to say before delivering his class. It is very rare to find a book so valuable to both beginners as well as seasoned scholars as the ArtScroll Talmud.

These two pivots—accessibility and applicability—themselves reflect the democratic ethos of daf yomi. While Torah study was always stressed in traditional Jewish circles, until recently the Talmud was a focus only for the intellectuals. Everyone else turned their attention to other texts: the Mishnah, Eyn Yaakov, Psalms. There are even rabbinic sources that state that non-intellectuals, who only have a limited time for study, should focus on practical halakhah. This makes a great deal of sense, for why should the average person devote time to arcane talmudic texts when he hasn’t yet mastered practical Jewish law? Yet daf yomi is revolutionary precisely because it has opened up the playing field, much as American universities opened up higher learning to the masses, teaching thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle to all. So too with daf yomi: Everyone is now welcome to study that which used to be the preserve of the elites.

Marc B. Shapiro holds the Weinberg Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Scranton.

_____________

The Joy of Talmud

By Gil Student

Many students are confused when they discover that Jewish law considers advanced Torah study a joyous act that is forbidden to mourners. They fail to see in their own lives how the study of God's words can "gladden the heart." But the Talmud is not just an acquired taste; it is also an acquired skill. The high school student breaking his teeth on a line of Talmud cannot imagine the intellectual delight a mature student finds therein.

The Talmud has a hard exterior but a soft and inviting inside. You have to spend years mastering the Aramaic and the unfamiliar structure of arguments, both concrete and abstract, in order to penetrate the ancient tome's shell. But at a certain level of mastery, there comes an inflection point. Suddenly, after years of word-by-word struggle, you can open a volume of Talmud and read it like a book. The vibrant debate comes alive as you are transported to Babylonia to witness the brilliant rabbinic exchanges. The sheer energy on the page is exhilarating.

Someone who has acquired the necessary skills can study a page of Talmud each day with relative ease. For such a scholar, daf yomi is an excellent tool for accomplishment and review. However, the thousands who lack the basic skills yet complete the daf yomi cycle accomplish something even more impressive: Even without the pure joy of Talmud, they heroically push forward and enjoy the sweet pleasure of completing the arduous holy task.

Rabbi Gil Student is a frequent writer on Jewish topics and maintains a popular blog at TorahMusings.com.

_____________

The People of the Tome

By Emanuel Feldman

It’s 5:30 a.m. in the dead of winter, still pitch black. A man makes his way through the freezing rain of Boston and opens a door. Inside, 15 other men are waiting. They are not gathered to eat breakfast or to have a beer—far from it. Before them sits a teacher, and they each open a huge tome, one of the most esoteric, abstract, fascinating works in the history of mankind: the Babylonian Talmud.

This scene is repeated every day, 364 days a year (the pleasures of Torah study are not permitted on Tisha b’Av), in cities as diverse as London, Paris, Johannesburg, Melbourne, Moscow, Odessa, Cape Town, and Amsterdam, plus dozens of cities in the U.S. and numerous locations in Israel. Everyone, everywhere is studying the same page.

That so many tens of thousands around the world attend the daily daf demonstrates that the Jews are indeed the People of the Book. Can you imagine Greeks gathering early every morning, through winter rain and summer heat, to study Plato line by line? Do Englishmen assemble in the thousands to analyze Milton or Shakespeare? Truly, mi k’amkha Yisrael—Who is like Thy people Israel.

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman is Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Beth Jacob in Atlanta. He is a former Vice President of the Rabbinical Council of America, and for thirteen years was the Editor of Tradition. The author of nine books and over 100 published articles, he was ordained by Baltimore’s Ner Israel Rabbinical College and holds a PhD in Religion from Emory University.

1) It was not a Hasidic yeshiva. It was a yeshiva with Hasidic and

non-Hasidic students.

2) Modeled after Volozhin and the Lithuanian yeshivot, its aim was to

introduce such institutions to Poland; this had nothing to do with

Hasidism.

3) The introduction of the dormitory and dining hall was made in 1803

with the opening of the Volozhin Yeshiva, and it was the standard

feature of all Lithuanian yeshivot that Volozhin spawned thereafter.

Lublin invented nothing new here. The novelty was only the territory,

i.e. Poland rather than Lithuania.

As for dormitories and dining halls: There were no such things in Volozhin. Students rented rooms from local townspeople and used yeshiva stipends to pay for food.

On both of these issues, see the extensive work of Shaul Stampfer on the social history of yeshivas in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In this we resemble Islam more than I find comfortable to bear.

No wonder women seek literacy elsewhere.

with the opening of the Volozhin Yeshiva, and it was the standard

feature of all Lithuanian yeshivot that Volozhin spawned thereafter."

Wrong. No Lithuanian yeshiva, and this includes Volozhin, had a dormitory and dining hall.

The gemoro is the central and most important contribution of the Jewish people to civilization but, unfortunately, will never be appreciated for what it truly is, the most brilliant journey into thinking and learning ever created, unless one learns the language, concepts and, above all, the methodology to penetrate and appreciate it.

Learning Torah = learning gemoro.

The satisfaction of really learning a daf gemoro, working through all the nuances with the greatest minds in civilization over the last two thousand years, is simply unimaginable for those who haven't experienced it.

I have multiple degrees from famous universities and love my work as a physician but gemoro, ah, that is something else entirely.

For those of you who find it hard to relate to the enthusiasm of some of the writers, check it out.

BTW, I am not frum, not orthodox, but I love gemoro.

http://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/en/home.html

That being said, I do agree that anyone who claims to have mastery of the Talmud (or Torah) by just learning the Daf Yomi at an accelerated pace is being disingenuous and fooling himself. Any such self-congratulatory claims are off-the-mark. While Daf Yomi might be part of one’s personal program of Torah study, I would see it as insufficient. It must be supplemented with iyun of the same Talmudic material, in addition to topics in Tanach, Halacha, and Machshava. There are many opportunities for shiurim or collaborative modes of study to support this.

Would Rav Aharon Kotler be happy with such a Siyum and his adherents celebrating it? We will obviously never know for sure. But you may be correct as it would be intellectually inconsistent with the in-depth study which characterized his approach. (This point is really a re-formulation of the Bekiut vs. Iyun debate which has existed since the days of the Talmud itself. The answer is really ‘yes’ and ‘yes’.) One might also wonder whether he would be happy with the large numbers of students currently in his Yeshiva, as it likely exceeds the objective percentage in the population who can keep up with the level of rigor that he demanded. At the end of the day, beyond any quest for ideological consistency, how he would weigh in is a moot point.

All in all, my take-away from the Siyum is that programmatic flaws aside, it was a great celebration of Torah which brought together Jews of many types. Furthermore, it brought the Torah to many who because of upbringing or the pace of life did not have it within reach. And for that, it was a good thing.

Comments are closed for this article.